Hong Kong as a global hinge

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Last week, President Xi Jinping announced plans in Shenzhen for the deeper integration of Hong Kong and mainland China. Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam postponed her scheduled annual policy address to attend the speech.

Less than halfway into the 50-year handover period that started in 1997, the ‘one country, two systems’ approach implemented in Hong Kong has de facto ended. The National Security Law was passed by Beijing in June despite mass protests, China is clamping down on opposition in Hong Kong, and Hong Kong’s independent institutions are being hollowed out.

Hong Kong is a canary in the mine

These developments matter for political freedom and democracy. Hong Kong’s experience also highlights dynamics at work in the global economy, acting as a small economy ‘canary in the mine’.

Hong Kong is a good indicator of the strength and nature of globalisation. The regime change underway in the global system runs directly through Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s economic model has been based on being an open, liberal hub for trade and capital flows, and serving as a location for companies doing business with mainland China – as well as outwardly-focused Chinese companies.

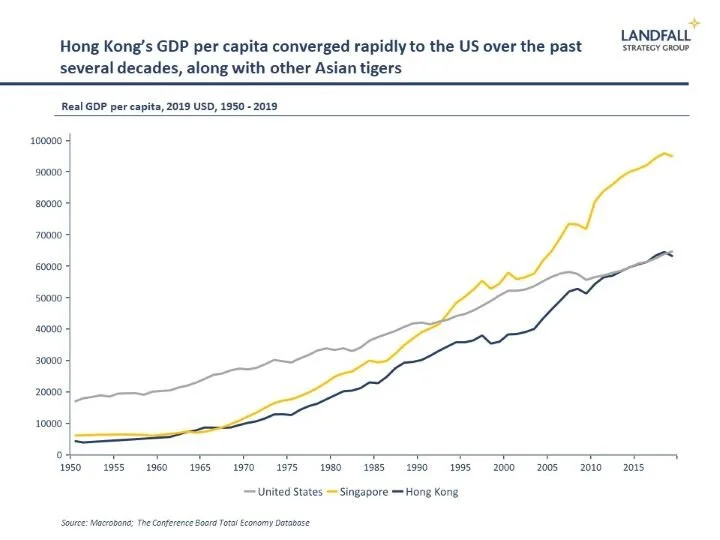

This model worked enormously well for several decades from the 1960s, with Hong Kong converging rapidly towards the global income frontier, along with other East Asian tiger economies.

Hong Kong has been a primary beneficiary of intense globalisation and the growth of Asian emerging markets, notably China.

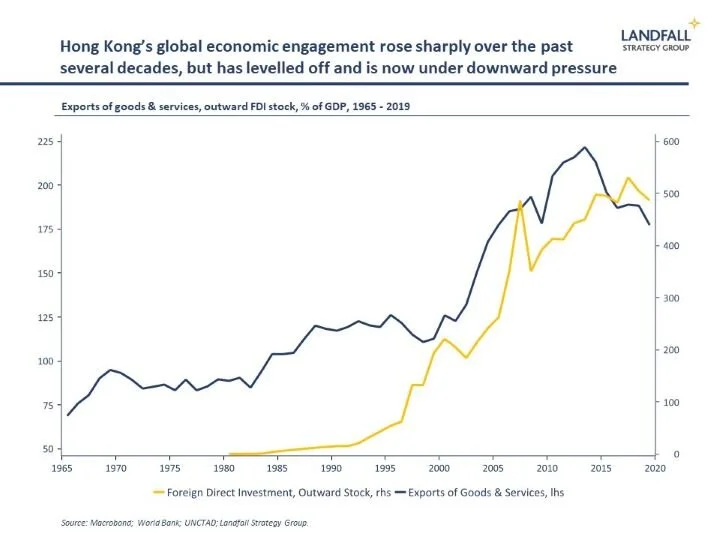

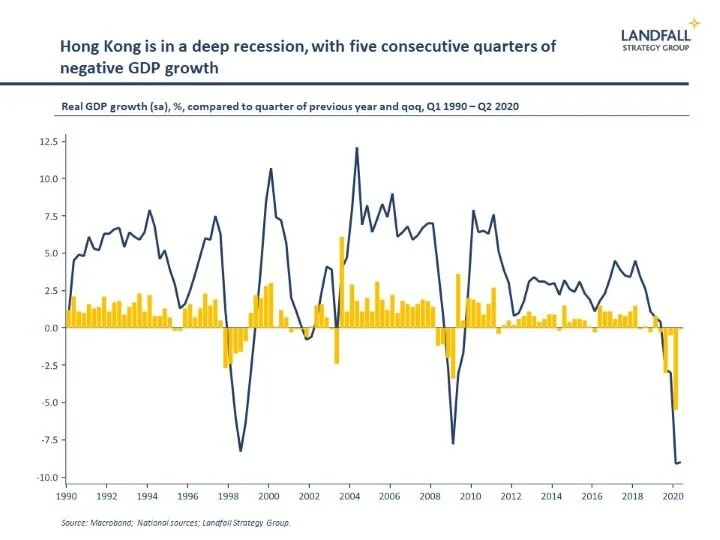

But as the intensity of global trade and investment flows has reduced over the past decade, so has the growth in Hong Kong’s internationalisation profile. And Covid-19 is having a severe impact on flows through Hong Kong, as seen in the collapse in passenger traffic at Hong Kong airport.

The economic and political integration of Hong Kong into mainland China changes Hong Kong’s positioning in a more fundamental way. Independent institutions will be changed over time, from the rule of law to exchange rate arrangements.

The US has withdrawn preferential trade access from Hong Kong, and there are numerous examples of firms and investors reducing their Hong Kong footprint.

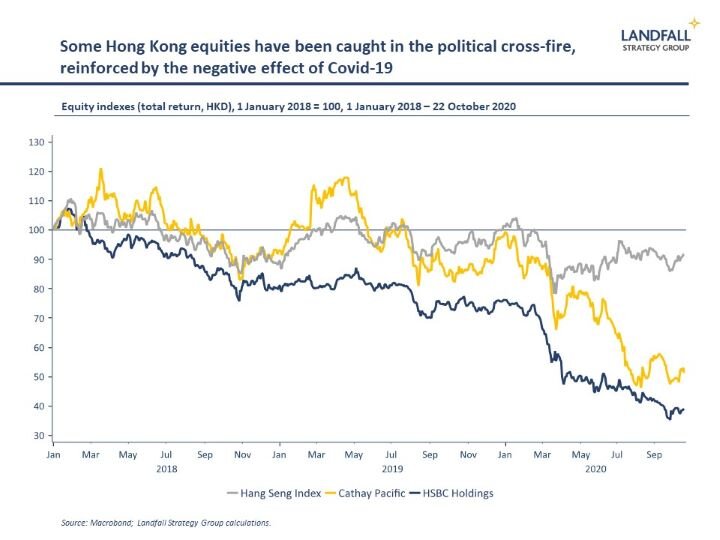

Companies from HSBC to Cathay Pacific have been caught in the cross-fire, being required to support the national security law. These political tensions are weighing on their share prices, alongside the effect of Covid-19.

These developments in Hong Kong parallel the trajectory of globalisation. The 1997 handover took place during a period of hyper-globalisation, and we are now experiencing regime change in the global economy. The emerging system of globalisation will have more frictions, be more regionally oriented, and will be more directly shaped by strategic political considerations.

The US/China trade wars, the use of economic sanctions, and supply chain nationalisation, are examples of this. Globalisation will be markedly different, a process accelerated by Covid-19 (discussed in my last note). These changes can be clearly seen in Hong Kong.

Responding to a changed strategic context

Hong Kong also provides lessons in terms of the importance of deliberately positioning for this new globalisation.

Over a sustained period, Hong Kong has made deliberate choices to position itself as a gateway to mainland China: investing heavily in infrastructure into the Greater Bay Area, being a domicile for Chinese firms, and acting as a key node for the Belt & Road Initiative.

It has become increasingly like Shanghai and Shenzhen, losing its distinctive position.

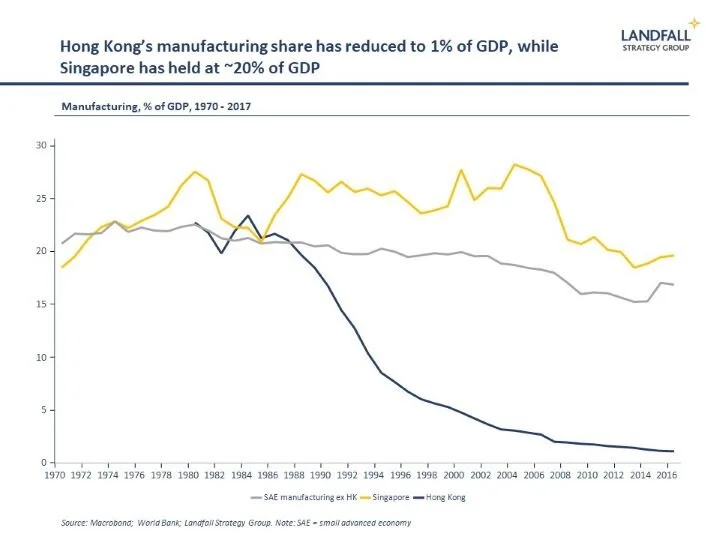

Hong Kong has chosen to double down on its hub strategy, becoming deeply exposed to external developments. Hong Kong did not develop the domestic capabilities and strengths seen in Singapore, another Asian city state, as I have noted previously: it has virtually no manufacturing or domestic exports of goods, low levels of R&D, and a heavy concentration on the Chinese market.

Although deeper economic and political integration with China was inevitable over time given Hong Kong’s economic geography and political situation, Hong Kong’s strategy accelerated the process.

This experience has implications for other small economies as they navigate through a changing global context.

First, there is a need to invest to sustain positions of strong competitive advantage. Without being distinctive, national economic and political relevance will decline. Economies from Singapore to Switzerland show how to maintain positions of global relevance despite their small size, and which provide a measure of strategic autonomy. Being a hub for global flows will no longer be enough.

Second, there is a need to keep options open – both by being distinctive, but also by building a diversified portfolio of relationships. This portfolio will always be shaped by geography, but in a more complex global system, small economies need to avoid being locked in.

Third, recognise that international politics increasingly matters for the design of economic strategy. Many small economies see this clearly, and are acting to manage the political dimensions of their economic relationships; for example, the new approaches of the Netherlands and Sweden to China.

Hong Kong’s trajectory is worth reflecting on to understand developments in the global system – as well as how to respond.

Chart of the week

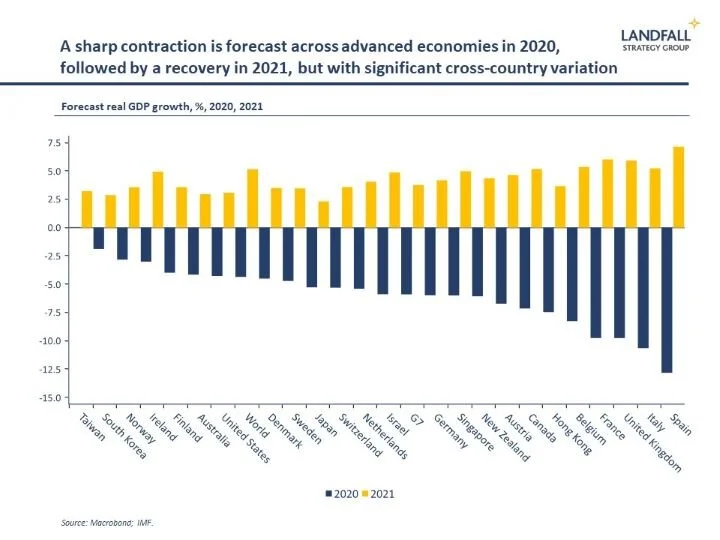

The IMF’s World Economic Outlook was released last week, with a slightly more positive assessment of global GDP growth: a contraction of 4.4% in 2020, before forecast 5.2% growth in 2021. Small advanced economies are expected to do slightly better over the forecast period; it is larger advanced economies that are hit hardest.

Elsewhere around the world

Singapore is another canary in the mine of the global economy. Advance estimates for Singapore Q3 GDP report 7.9% growth (qoq) in Q3, supported by resilience in external sectors, after a contraction of 13.2% qoq in Q2. But this is not (yet) a v-shaped recovery profile: Q3 GDP remains about 7% lower than in Q4 2019. My summary charts are available here.

An Irish budget ‘unprecedented in both size and scale’ was delivered, with significant measures to offset the economic impact of Covid-19. New spending measures of €18b of GDP were announced. Some budget measures were also to prepare for the growing risk of a hard Brexit, to which Ireland is deeply exposed.

New Zealand’s Labour Party won a landslide election victory, taking the first outright majority since the MMP voting system was introduced in 1996. The Labour Government was riding high on its record of eliminating the domestic spread of Covid-19 from New Zealand. A challenging term lies ahead though, as the focus turns to the economic recovery.

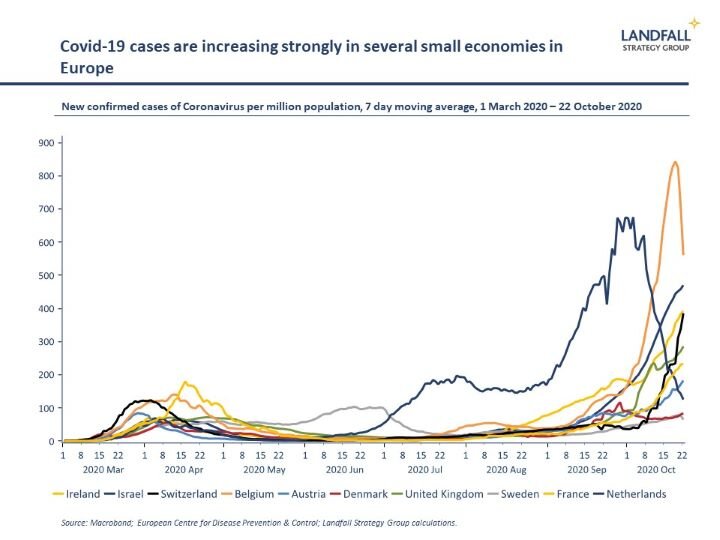

Second waves of Covid-19 continue in many small economies in Europe, which are often more pronounced than the first waves. This is partly due to governments and populations becoming overly relaxed after success in navigating the first wave. Belgium and the Netherlands now have among the worst records in Europe in terms of new cases per capita. And it turns out that Swiss yodeling is bad for Covid-19 outcomes. New lockdown measures are being implemented across Europe.

Some parts of the world are beginning to open up, even as Europe locks down again. Singapore and Hong Kong have agreed to open bilateral air routes, some Australian states are opening to New Zealand, and Singapore Airlines is resuming direct flights between Singapore and New York from November. But it will be a long way back for international aviation. Singapore’s massive Terminal 5, currently under construction, has been pushed back due to the massive uncertainty about the outlook for international air traffic.

Small economies such as Ireland, the Netherlands, and Belgium, are estimated to be particularly exposed to a hard Brexit because of the intensity of economic linkages. Flanders in Belgium is deeply exposed, offset by the right – granted in perpetuity by King Charles II in 1666 – for 50 fishing boats from Bruges to fish in English waters (and which is apparently still legally valid). It pays to have creative lawyers.

The Swedish government has announced plans to increase military spending by 40% by 2025, in response to growing threats from Russia. It will double the size of the compulsory draft (introduced in 2017) and increase military headcount from 60,000 to 90,000. And in Asia, Taiwan is facing increasing military threats from China. Invasion is still a tail risk, but the probability is not zero. In the meantime, Chinese diplomats are roughing up their Taiwanese counterparts.

Thanks for reading. You can subscribe to receive these notes by email. And feel free to share this with anyone that may be interested.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling