On Trump, democracy & getting to Denmark

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

The contested and noisy elections in the US this week, as well as the ongoing chaos of Brexit, confirm that 2020 is not a bookend to the political earthquakes of 2016.

The underlying issues that led to these political ruptures remain largely unresolved. Many voters wanted to ‘take back control’ from elites that they believed had set policy in a way that rigged the playing field against them. These sentiments remain widely held.

And substantial damage has been done to political institutions and trust in government in the meantime. President Trump’s behaviour and rhetoric – including his claims of electoral fraud – have worsened political dysfunction and polarisation. There is no status quo ante to return to.

These institutional problems extend well beyond the US and the UK. A recent Cambridge University study documented a substantial decline in trust in political institutions, with a majority in developed countries saying that they were not satisfied with democracy in their countries (> 60% in the UK, Italy, and Spain, > 50% in the US and France).

However, there are notable exceptions. The study notes that ‘Many small, high-income democracies have moved in the direction of greater civic confidence in their institutions. In Switzerland, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, for example, democratic satisfaction is reaching all-time highs’ (< 20% dissatisfaction reported).

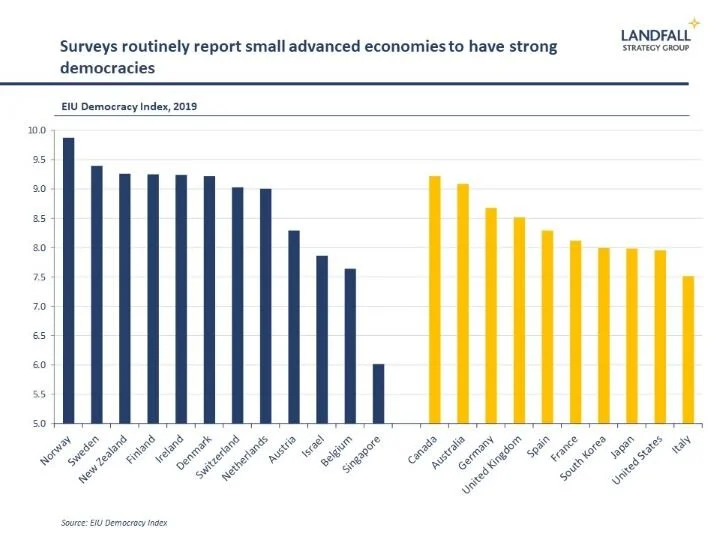

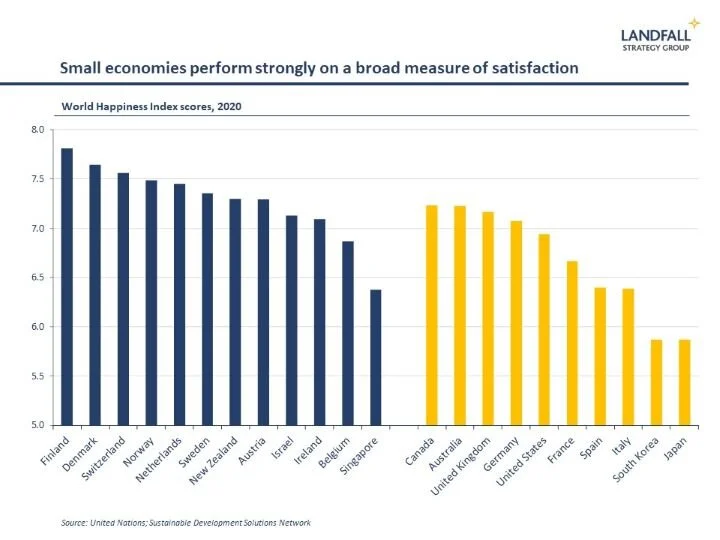

This finding is consistent with many other surveys that report strong democracies, and high levels of social capital and institutional trust, in small advanced economies.

More recently, many small economy governments have received high public support in opinion polls (and at the ballot box) for their handling of the Covid-19 crisis, from New Zealand and Scotland to Sweden and the Netherlands. Despite variation in performance, small economy governments have generally set policy in a way that has reflected public preferences.

This does not make small economies immune to political pressure; there has been an increase in the right-wing populist vote share over the past several years. But it provides a measure of resilience against political shocks.

Why do small economies perform better?

The higher level of political transparency and accountability in small political units helps to sustain institutional trust, as well as trust across society.

But at least as importantly, institutional trust is high in small economies because these political institutions have delivered good economic and social outcomes. Small economies have performed well in terms of GDP growth, employment, income inequality, social mobility, and so on.

Many small advanced economies have been able to deliver inclusive growth, managing to capture the gains from globalisation and technology while managing the risks and costs. The political backlash in many large economies is not to globalisation but to the absence of an effective policy response. Perhaps ‘incompetence is the real threat to democracy’.

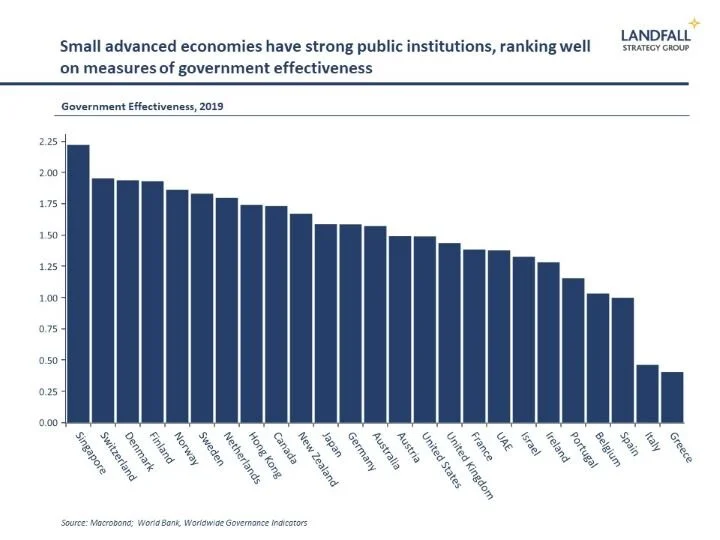

This performance has been supported by strong state capability. Small advanced economies dominate rankings of institutional quality, such as the World Bank’s effective governance measures, the corruption perceptions index, as well as measures of economic institutional quality.

Why does this matter?

Governments face a range of structural challenges and opportunities: inequality and unemployment, weak productivity growth, climate change, and so on. These pressures have been reinforced by Covid-19.

In addition to high levels of state capacity, an effective response to these priorities will demand the ability to make hard political choices. This will require a high level of institutional trust. In turn, this means that strong social and political institutions will become an increasingly valuable source of competitive advantage.

Countries with the strongest institutions will be able to move more quickly and effectively in response to shocks. This was the case after the global financial crisis, and seems also to be the case with the Covid-19 response. For example, countries with high levels of trust in government have seen higher levels of compliance with Covid-19 restrictions.

The strength of social and political institutions in small advanced economies provides them with an edge as they confront a more challenging world. They have high levels of exposure to economic shocks, but small economies have much lower levels of domestic policy and political risk.

In contrast, large countries with weak institutions have feet of clay. At some point the institutional weaknesses seen in the US and China will catch up with their economic dynamism, by constraining their ability to adapt to emerging challenges. A correspondingly higher risk premium should be applied to these larger countries.

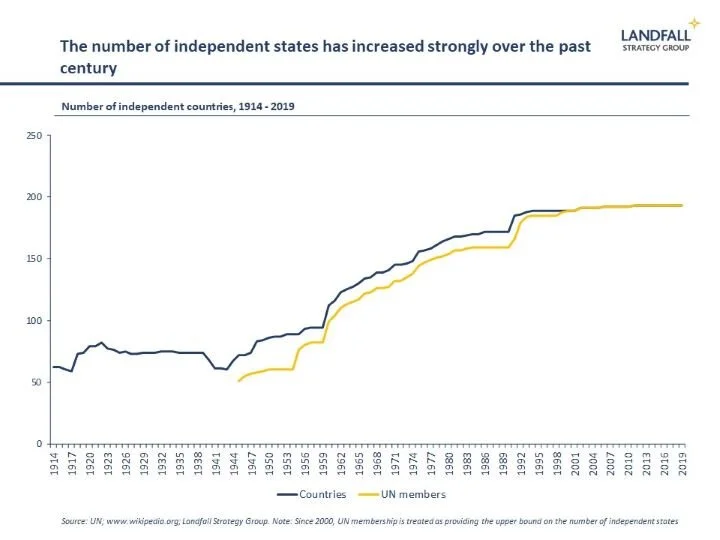

The future is small

Although much is made of the importance of national scale in an era of competing economic and geopolitical giants, the institutional advantages in small states will lead to a lowering of the centre of gravity of decision-making.

We should expect centrifugal pressure for political devolution from the centre, and increased support for independence movements (as in Scotland) in some cases, to improve outcomes and democratic legitimacy. And limits will be encountered on centralising political projects.

American political scientist Francis Fukuyama identified ‘getting to Denmark’ as the lodestar for a prosperous, well-governed society.

President Trump’s primary interest in Denmark seemed to be negotiations to purchase Greenland. He should have looked harder. There are a broader set of insights to be taken from Denmark – and other small advanced economies – in terms of how to organise successful societies.

Chart of the week

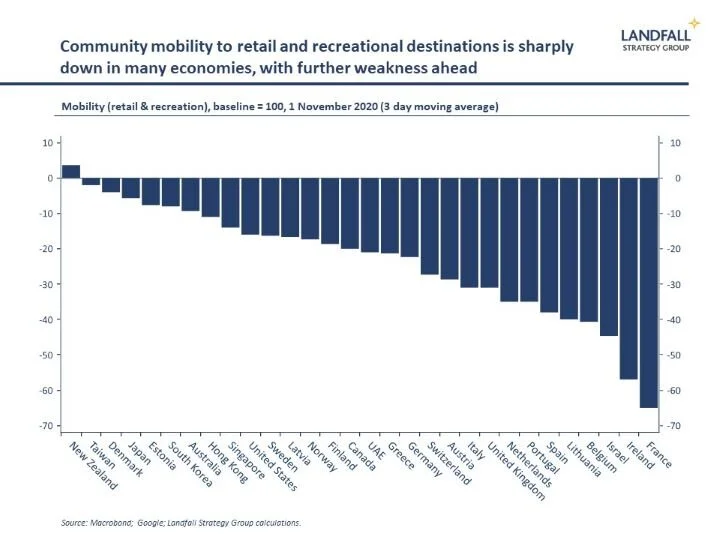

Concerns about Covid-19 as well as increasingly widespread lockdown measures have reduced mobility according to data from Google, particularly in Europe. Retail and recreation mobility is down by over 50% in countries like France and Ireland relative to baseline, although it is up in New Zealand and only modestly down in many developed Asian economies and the Nordics. Worse is still to come as further lockdown measures are implemented in Europe, which will mean a weaker Q4 after a recovery in Q3.

Around the world

Small economies are putting their hands up for the next Secretary General of the OECD. Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Sweden, the Czech Republic, and Switzerland have nominated candidates – and the United States has nominated dual New Zealand/US citizen Chris Liddell, currently Deputy Chief of Staff in the White House. I have argued before that a small economy voice would add value to organisations like the OECD (see this Wall Street Journal op-ed): small economies are policy innovators and have managed globalisation well.

Small economy policy innovation has been seen through the Covid-19 experience. Estonia’s heavy investment in digital education (and digital government more broadly) has allowed it to respond effectively to the shift to greater online schooling over the past several months. In monetary policy, Israel is implementing targeted loans for banks at negative interest rates (with conditions) – and New Zealand is thinking about following other small economies in implementing negative policy rates.

Small economies are innovating in Latin America as well. A referendum in Chile to draft a new constitution passed with 78% support. A process to draft a new constitution by 2022 is now underway. This was sparked by mass street protests last year. Across the Andes, Uruguay is attracting people from Argentina – tax advantages, quality of life, and better governance.

New EU minimum wage proposals are riling some small European economies, notably Denmark and Sweden. Although these countries have high wages and protections, their systems rests on well-established social bargaining systems – and there are concerns that these proposals would cut across this model. This is another example of small economy pushback against centralising tendencies in the EU.

There is a pronounced second wave of Covid-19 cases in Europe and the US, with many governments imposing lockdowns. But Taiwan has been 200 days without a case, New Zealand and Singapore have essentially no community transmission, and Slovakia is testing all of the adult population in the country (twice).

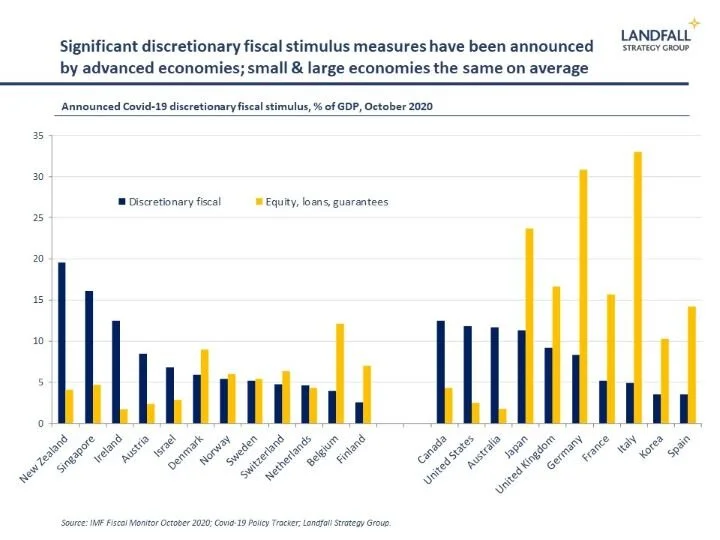

The IMF report that small economies have committed substantial amounts of discretionary fiscal stimulus in response to Covid-19, led by New Zealand and Singapore (20% and 16% of GDP respectively). This was supported by strong fiscal positions, but this experience suggests that small economies are not deeply disadvantaged in responding to economic shocks.

Thanks for reading. You can subscribe to receive these notes by email. And feel free to share this with anyone that may be interested.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling