Small economies in a post-Covid world

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here.

The OECD’s recent Economic Outlook forecast a contraction in world GDP of 4.5% in 2020 before a recovery from 2021.

Covid-19 is also strengthening structural dynamics that will profoundly shape the medium-term economic outlook - as well as the most effective growth models - across economies.

Governments, firms, and investors will need to respond to at least three structural dynamics. Covid-19 will advantage or disadvantage different sectors (e.g. technology v international tourism); will tend to advantage capital and knowledge intensive activities relative to labour intensive activities; and will place pressure on activities exposed to the existing model of globalisation.

In addition to driving a ‘k-shaped’ recovery process within economies, discussed in a previous note, exposure to these structural dynamics will drive variation in economic performance across economies. There will be clear national winners and losers.

Sectoral exposures

The structural growth outlook across sectors has widened because of Covid-19, and national economic outlooks will be shaped by their portfolio of sectoral exposures.

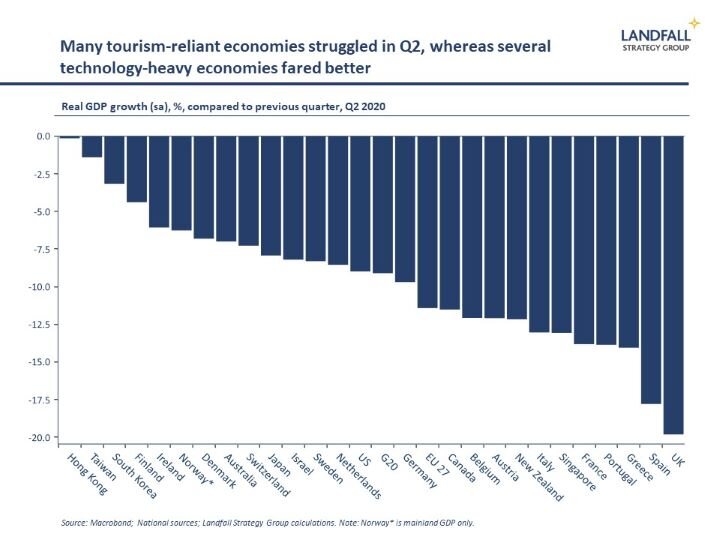

Economies with a high level of exposure to international tourism will be challenged, for example, whereas technology heavy economies will be supported. This can be seen in the Q2 GDP data: tourism-reliant countries like Greece, Portugal, and Spain were hit hard, whereas technology-exposed South Korea and Taiwan did relatively well.

These sectoral effects will endure well beyond the initial crisis period, and economies will need to rebalance their sectoral footprint in response. New growth engines need to be developed to sustain strong outcomes given new patterns of global demand.

Capital & knowledge intensive growth models

Several of the sectors negatively impacted by Covid-19 (international tourism, physical retail) tend to be labour intensive with relatively low labour productivity. In contrast, technology or clean energy are more knowledge and capital intensive. And the rise of the ‘contactless economy’, from retail stores to the factory floor, places further pressure on labour intensive models.

Generating economic value from technology and knowledge is not new of course, but it will be increasingly important in a post-Covid world.

Across advanced economies, there is wide variation in growth models. Some rely on labour force growth to generate GDP growth (e.g. New Zealand), while others (e.g. Denmark) rely more on labour productivity growth – supported by investment in physical and human capital as well as innovation.

Those advanced economies with weaker investment and labour productivity will face a more demanding transition process to a capital and knowledge intensive growth model. Substantial public and private sector investment in skills, R&D, and physical capital will be needed.

And this process needs to be managed in an inclusive way so that increased investment in technology and knowledge augments rather than replaces labour. This will be complicated by the expected high levels of unemployment, but the transition to a high skills, high investment, high productivity economy is an imperative.

Many small advanced economies, such as the Nordics, provide useful examples of running high productivity economies in inclusive ways.

Changing globalisation

Small economies are also exposed to changes to globalisation, from trade wars and economic sanctions, to a new global geography of supply chains due to technology and political pressures.

Covid-19 will reinforce this, with a greater commercial and political focus on the resilience of supply chains and on national autonomy. National growth models cannot simply rely on a rising tide of globalisation.

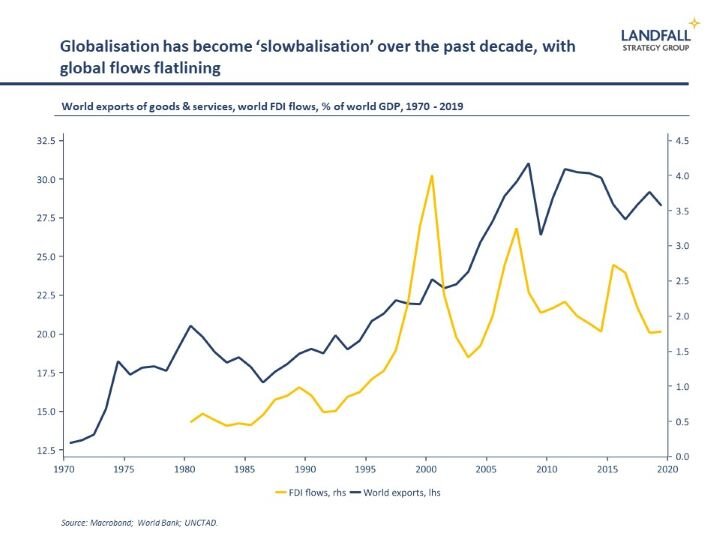

Indeed, on standard measures, globalisation peaked over the past decade – with GDP shares of world trade and FDI flows moving sideways. And this week the WTO forecast a 9% contraction in world trade in 2020 before a recovery from 2021.

But my assessment is that globalisation is changing, not ending. Countries that develop positions of distinctive competitive advantage can continue to do well. An internationally-oriented growth strategy is still credible – and a necessity for smaller economies – even in a more challenging global environment.

Open economies will need to adapt to a new global economic geography and changed sectoral demand profiles. Although being a hub for cross-border flows will be challenged (Dubai, Hong Kong), developing competitive positions in growth sectors will be an ongoing source of advantage (Denmark, Switzerland).

A broader distribution of outcomes

The structural dynamics associated with Covid-19 will have a material impact on national economic performance. These pressures also mean that a k-shaped economic recovery profile across advanced economies is likely, with significant variation in economic performance.

Many small advanced economies seem well-positioned despite their direct exposure to the strength of globalisation. Their high levels of human capital and innovation capability provide a good basis for more technology and knowledge intensive modes of production.

And small economies are effectively navigating a changing globalisation so far with many generating resilient export performance on the back of strong competitive positions. Indeed, there are some benefits: technology will allow some small advanced economies to retain economic activity rather than offshore it (e.g. automation in the high cost Nordics).

Most small advanced economies have been resilient to global economic and political shocks over the past century, adapting their growth models to new contexts. They will need to do so again.

Chart of the week

Small advanced economies have a high number of world-class universities on a per capita basis, as measured by the (much debated) Times Higher Education rankings for 2021. The Netherlands has 11 universities in the top 200, and Switzerland has 7.

Around the world

Sweden, as well as the other Nordics, are expected to have much milder GDP contractions in 2020 than other European countries. This is likely more about economic structure and competitiveness than simply the relatively light touch lockdown measures.

Singapore is investing heavily in the digital transition in part to respond to structural changes in the nature of global flows. PM Lee noted that ‘We will not be returning to the open and connected global economy we had before any time soon… (and will need to) prepare for a very different future’.

Switzerland held a series of referenda last week: 62% voted against limits on EU migration, removing a potential source of tension in relations with the EU. The Swiss also voted to spend CHF6 billion on new fighter jets, and in favour of paid parental leave. And voters in Geneva agreed to raise Geneva’s minimum wage to CHF23/hour (~USD25/hour), the highest in the world.

China’s reputation slides in small countries. A survey of attitudes towards China in 14 advanced countries found China’s soft power at all-time lows. There were sharp increases in unfavourable ratings since 2019 in Sweden (the target of significant Chinese pressure), from 70% to 85% of respondents, and the Netherlands – from 58% to 73%. Denmark and Belgium, included for the first time, reported unfavourable scores of 75% and 71%. These countries also reported low favourability ratings for the US.

It took much more than four seasons but Belgium finally has a permanent government. The ‘Vivaldi coalition’, comprising seven parties, took 652 days to assemble after the collapse of the previous government in December 2018. This beat the previous record of the 589 days it took to negotiate a government in 2010/11.

Even microstates are caught up in big power politics: the US is pushing the Vatican not to move forward with its diplomatic outreach to China

Swiss central bank intervention hit CHF89 billion in the first half of 2020, as it continues to alleviate upward pressure on the CHF – a currency it already regards as over-valued. The SNB’s balance sheet has grown to over USD1 trillion, including significant holdings (~USD120 billion) of US equities.

Other writing

I had a recent piece in New Zealand’s Dominion Post on the priorities for creating a dynamic Wellington economy – drawing on my research into the challenges and opportunities facing ‘second cities’ in small advanced economies.

Thanks for reading. Please subscribe if you would like to receive future notes by email, and feel free to share this note with others.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling