Spring time in the global economy

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

The early spring weather in Europe may have been interrupted by too much snow and hail, but it is the time of the year for optimism. And I am as optimistic about the global economy as I have been for some time.

The remarkable speed of developing effective vaccines, together with substantial fiscal stimulus (notably from the US), is providing support to the global economy. The two extra Senate seats for the Democrats in Georgia turn out to have had a global impact.

The IMF’s new World Economic Outlook contains significantly upgraded growth forecasts, particularly for advanced economies. World GDP growth for 2021 was marked up from the IMF’s October forecasts by 0.8% to 6%; and for advanced economies by 1.2% to 5.1%.

Getting to v

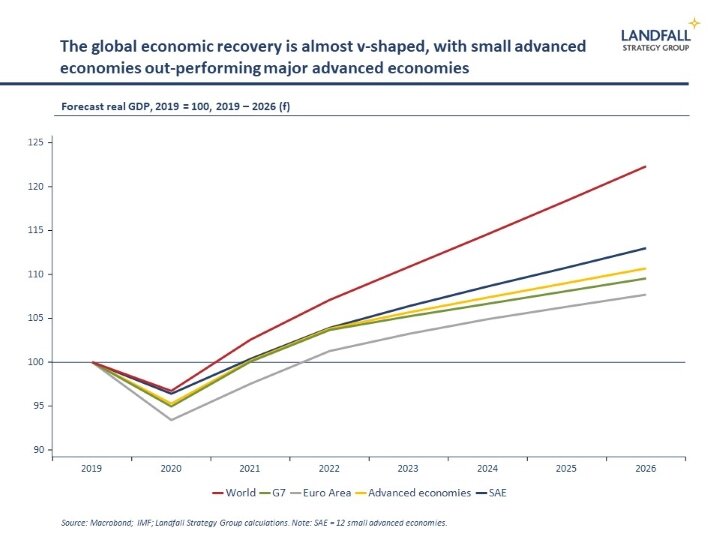

This is not quite a v-shaped process; many economies will take until 2022 to return to their 2019 GDP levels. And the lost output will not be fully recovered. But the global recovery is much more v-shaped than I would have picked six months ago, with positive surprises on vaccines and macro policy. It will be a sharper recovery than after the global financial crisis, particularly for advanced economies.

One measure of this is the resilience of globalisation. World trade is back above pre-Covid levels, as discussed in my last note.

All of this is good news for small advanced economies, which are deeply sensitive to the strength of the global economy. Indeed, small economies are expected to out-perform over the forecast period; a shallower recession through 2020, followed by a reasonable recovery. Equity markets in small economies that are most sensitive to the global economy have performed well this year.

Over a longer time horizon, there are also reasons for optimism on the global economic outlook. I am increasingly persuaded by the likelihood of a post-Covid productivity renaissance that I first discussed last year. A recent MGI paper identified stronger productivity growth as a plausible scenario, citing accelerated investment by firms.

The interaction of macro stimulus with the supply-side potential could lead to sustained above-trend growth rates. Labour productivity growth rates across advanced economies have declined for the past few decades; they averaged ~1% over the past decade compared to ~2% in the period from 1990 - 2005. A return towards 1990s productivity growth rates is an aggressive target but not completely unreasonable.

Lifting all boats in a rising tide

But this positive economic trajectory is not equally shared. The IMF notes the higher economic costs that have been incurred by emerging and developing countries relative to advanced economies that have greater access to vaccines and fiscal policy space.

And in a more structural sense, the post-Covid world could create some challenges for the growth models used in many emerging markets (as I recently noted). This could weaken the income convergence process. This will require both domestic and international policy action.

And within economies, income and wealth inequality has worsened during the crisis despite the fiscal and labour market policy measures. This will need to be a direct object of policy, both to secure better outcomes as well as to manage the associated political pressures. This was not done sufficiently after the global financial crisis, but the global policy consensus has shifted in a generally positive direction since.

Over time, there is also an argument that these gains will be more broadly shared (see this Economist lead), with the labour income share increasing over time (due to higher wages and supportive labour market policy). This is a possible outcome, and there is some historical precedent.

But it will require major policy support to make it happen given the labour market impact of new technologies and the Covid hit to labour intensive sectors.

Policy actions around skills and training, investing in infrastructure, and creating new growth and employment engines (digital, green) are encouraging. From Singapore to Ireland, Greece and beyond, there are deliberate efforts to position economies for a new world.

Risks

With any Goldilocks scenario, we shouldn’t forget about the possibility of hungry bears lurking outside.

First, economic risks to the outlook could come from delayed reopening (new variants, more delays to vaccinations) as well as the potential for a sharp rise in interest rates. Low interest rates have provided additional fiscal space for governments to respond; ongoing increases in interest rates could constrain this ability, particularly in high debt counties.

Second, the domestic political environment shaped the quality of the response to Covid through 2020. This will also be the case in the recovery phase. And there are risks.

Although the Biden Administration is moving rapidly and effectively – and with strong approval ratings – the US is deeply divided, and the window of opportunity for policy action may close with the 2022 mid-term elections. Elsewhere, Ms Le Pen is polling strongly in France, and there are many and varied political challenges in the UK. The current political calm in major advanced economies may not last.

Third, the geopolitical environment – from Taiwan to Iran and the Ukraine – creates a series of wild card risks. Geopolitical risks have not meaningfully shaped the recent global economic trajectory, but they should not be ignored.

But overall, I am upbeat on the global economic outlook over the next several years. And the European spring weather forecasts are also improving!

Get in touch if you would like to discuss this analysis and its implications. I am also available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

The IMF reports substantial fiscal loosening across advanced economies in response to the Covid shock. However, small economy governments are projected to move back close to fiscal balance over the next several years, controlling gross government debt at around 60% of GDP. This contrasts with the average advanced economies level of gross debt at around 120% of GDP; and the G7 at about 140% of GDP. This is despite small economies providing aggressive discretionary fiscal stimulus through 2020: over 8% of GDP on average.

Around the world in small economies

Singapore is a canary in the mine of the global economy. Advance estimates for Singapore’s Q1 GDP growth released during the week reported better than expected 2.0% qoq growth – for 0.2% on the year to Q1. Manufacturing activity remains strong, and services activity is recovering as restrictions are lifted. The official forecast of 4-6% GDP growth for 2021 remains, although the MAS expects GDP growth to exceed the upper bound of this forecast range.

Hong Kong is making efforts to bring manufacturing activity back, after an almost complete exit over the past few decades, providing subsidies and other policy support. This Bloomberg piece draws on my analysis of economic policy in Hong Kong.

Norway’s $1.3 trillion sovereign wealth fund has released its Strategy Plan for 2021/22. Among other things, it announced investments of $14b in clean energy infrastructure – it has just agreed a $1.6 billion deal to buy 50% of the world’s second-biggest offshore windfarm from Denmark’s Orsted. And it is increasing its appetite for active management, a big deal since the fund holds 1.5% of all global equities.

Nordic countries are moving from being aggressive adopters of electric vehicles to developing capabilities in the supply chain – using their renewable energy supply to develop positions in battery manufacturing, which is an energy intensive process.

The Dutch National Growth Fund, with a budget of €20b, has made an initial set of funding commitments. These range from rail infrastructure (to better connect Schiphol Airport to Amsterdam) as well as big investments in hydrogen, AI, and quantum technology, areas in which Dutch firms are developing an edge.

Singapore’s political transition process has encountered some turbulence. The designated successor to current PM Lee – Deputy PM Heng Swee Keat – announced that he will not take on the role. The search is back on among the ‘4G’ group of leaders to find Singapore’s 4th Prime Minister since independence in 1965.

Lithuania has become the EU’s fastest growing fintech hub. The share of transactions administered by fintech companies rose to 27% in 2020 from 11% in 2019, and the central bank has registered 132 fintech and payments companies. Firms like Revolut have relocated to Lithuania from the UK after Brexit.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling