The Suez Canal, Coronavirus, & scale

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

The grounding of the Ever Given in the Suez Canal last week captured the world’s attention.

In addition to causing a deluge of ship-themed gifs, this was a consequential event. It generated substantial costs, congestion, and delays around the world – and created further pressure on shipping prices. Fortunately, the immediate economic impact was limited because of the speed of the successful Dutch firm-led salvage effort.

On globalisation

This event also provided an abundance of metaphors on globalisation. Most obviously, it is a reminder of the vulnerability of global supply chains. Ships transiting the Suez Canal carry $10b in trade a day, from consumer goods to oil and gas, accounting for 12% of world trade. The closure of this global trade artery for six days raised concerns about global economic resilience.

The CEO of AP Moller Maersk said during the week that ‘We are moving towards a just-in-case supply chain, not just-in-time. This incident [in the Suez Canal] will make people think more about their supply chains’. Running efficient, just-in-time processes creates exposures to supply chains disruptions, as a recent McKinsey Global Institute report shows.

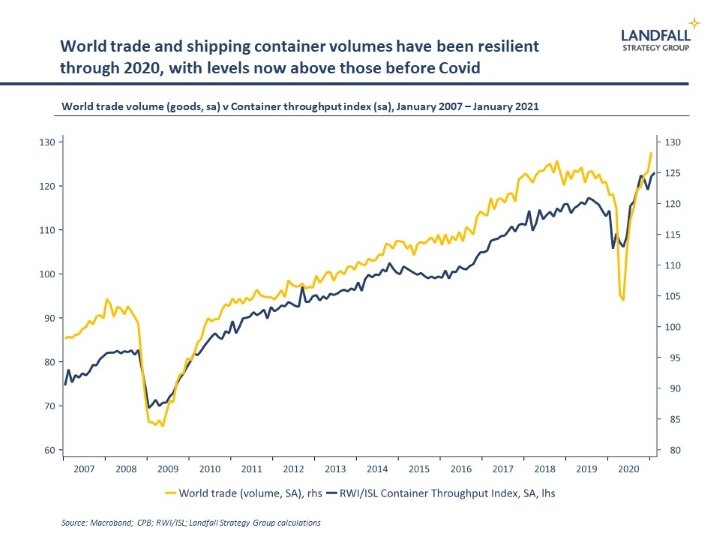

But globalisation has proven to be relatively resilient, and change will likely be evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Despite Covid, world trade has continued to grow strongly. And there is little at-scale evidence yet of significant supply chain relocations. Over time though, commercial and political factors are likely to shorten supply chains and lead to a more regional global economy.

On diseconomies of scale

To me, the striking takeaway of this incident is the impact of scale. The Ever Given was one of the world’s largest ships, carrying >20,000 20-foot containers.

The interaction of the ship’s scale with the wind looks to have been a key cause for the grounding. The hydrodynamics of large ships in narrow canals create particular issues for maintaining control. As ships get larger, the risks grow.

The largest container ships have increased by a factor of ~3x over the past 20 years, due to a drive for lowering cost per container and emissions intensity in an era of rapid world trade growth. The biggest container ship today is 24,000 TEU, 20% bigger than the Ever Given. And bigger ships are planned.

There is a point at which broader diseconomies of scale begin to kick in, with scale creating additional costs and risks and reducing flexibility. For example, the growing scale of these container ships creates domestic issues in terms of infrastructure. The demise of the A380 is another example of an ultimately misplaced focus on scale (great though it was to fly on).

Similar dynamics can be seen at political level. In an age of geopolitical giants and growing frictions on globalisation, a premium is often attached to scale. But larger political units often do not generate better outcomes (economic, social), are more difficult to manage, and – outside of areas such as the expression of hard power or regulatory standards – do not frequently benefit from economies of scale.

As one example, smaller economies have had generally better Covid experiences. In a review of Covid-19 management, the Lowy Institute noted that ‘smaller countries with populations of less than 10 million people consistently out-performed their larger counterparts throughout 2020’; I recently noted the stronger small economy GDP growth in 2020; and YouGov report higher levels of citizen satisfaction with their government’s handling of Covid in multiple small economies.

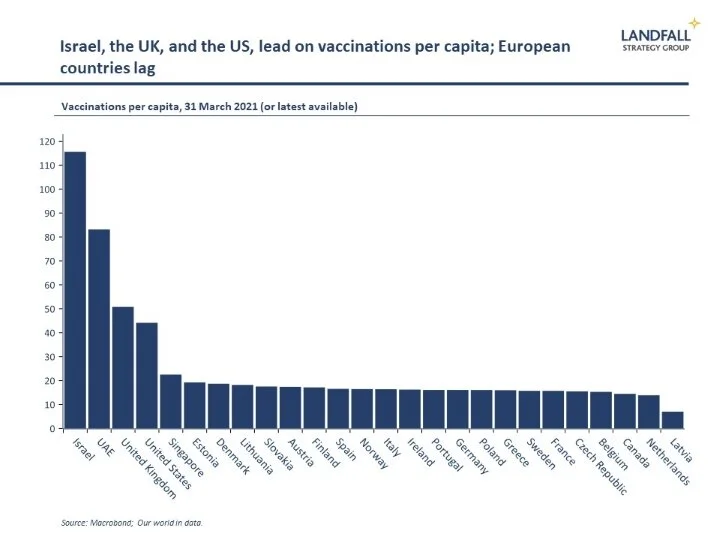

And consider the EU’s vaccine procurement programme. It made sense in principle to negotiate centrally rather than having 27 EU governments competing with each other. But if the Commission takes this responsibility, concentrating risk, it needs to deliver. And it hasn’t.

Of course, there is plenty of blame to go around. Many European national governments have not acted with urgency, and domestic logistical problems abound. But as the UK and Israel show, smaller size, responsiveness, and higher risk tolerance have worked well (the US is also moving fast after a slow start).

In general, the agility and flexibility of smaller political units, supported by strong political institutions and high quality decision-making, more than offsets any economies of scale.

Geopolitics & scale

But as with container ships, large scale dominates in the global system. About 60% of world GDP (in USD terms) is accounted for by countries with populations of >100m. The US and China alone account for >40% of global GDP. In contrast, my group of 12 small advanced economies account for 6% of global GDP (just above Japan).

These realities can create pressure to build larger blocs. For example, former European Commission President Barroso once noted that ‘in a world of giants, size matters’, the implication being that deep European integration was needed for relevance.

But as the Ever Given experience reminds, bigger is not always better. The edge is just as likely to belong to the smart and agile as to the large. Decentralised approaches can strengthen both performance and resilience.

In the EU context, this suggests caution in pushing centralising initiatives: from creating a ‘geopolitical Commission’ to strengthening the role of the euro by issuing EU-wide debt. There can be good reasons to bulk up by deepening integration but the case should be made not assumed or asserted.

Indeed, the large size of both the US and China is a source of both national and systemic risk. We should not be seduced by scale.

Get in touch if you would like to discuss this analysis and its implications. I am also available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

The 2021 edition of the World Happiness Report has just been released, an annual index prepared by a team of respected academics. Finland ranked first again, proving that weather is no obstacle to happiness. And the top ten positions were all filled by high-performing small economies: the Nordics, the Netherlands, Switzerland, New Zealand, and so on, demonstrating that strong economic performance and broader welfare can be complementary. In contrast, Asian economies registered weaker scores – Taiwan is an exception.

Around the world in small economies

The New Zealand Government announced new housing policy measures to try to constrain surging housing prices (+20% over the past 12 months). They removed the deductibility of interest for landlords, extended the period that a property must be held by investors to avoid capital gains being taxed, and committed extra funding for supply side measures.

The Irish Government announced policies to encourage people to work from small towns and villages, building on the greater appetite for working from home in a post-Covid world. They are proposing to build 400 remote working facilities around the country, invest in high speed broadband, provide tax breaks, and so on, to address regional imbalances.

Swedish fashion firm H&M is in Beijing’s crosshairs after it said that it would not source cotton from Xinjiang. H&M stores disappeared from online maps used in China, and there were calls (including in state media) for boycotts. Sweden’s relations with China have been tense for some time, and these actions are increasingly out of China’s playbook.

Recent elections in Israel and the Netherlands seem to have resulted in more of the same. There is deadlock again in Israel with no clear majority, and another election possible this year. And in the Netherlands, the election looks likely to have returned a very similar set of coalition partners as the previous government - but the coalition formation process is on hold because of Covid and a mistake by the negotiators.

Iceland has opened up to all tourists that have proof of vaccination, without requiring a negative test or quarantine, one of the first European countries to do so.

The World Economic Forum released its 2021 edition of its Global Gender Gap Report. Iceland is again the most gender equal country. The top 10 places in the index are taken by small economies, including Finland, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Namibia, Rwanda, Lithuania, Ireland, and Switzerland.

Greece celebrated its 200th anniversary of modern independence from the Ottoman Empire on March 25.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling