Dancing with the dragon

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

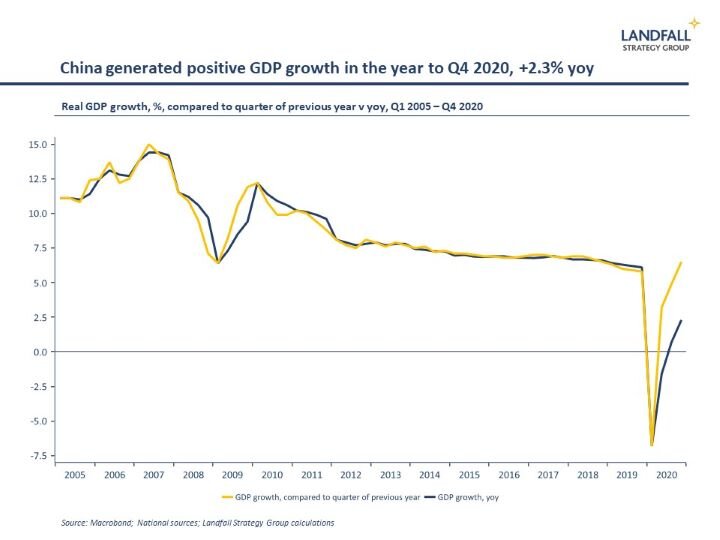

China reported quarterly GDP growth this week of 6.5% in Q4 2020 compared to Q4 2019, and 2.3% yoy. It is alone among major economies in generating positive GDP growth.

This is a function of the rapid return to economic normality from Covid-19, as well as government support; industrial production was very strong, unwinding attempts to rebalance the economy.

The rise of the Middle Kingdom

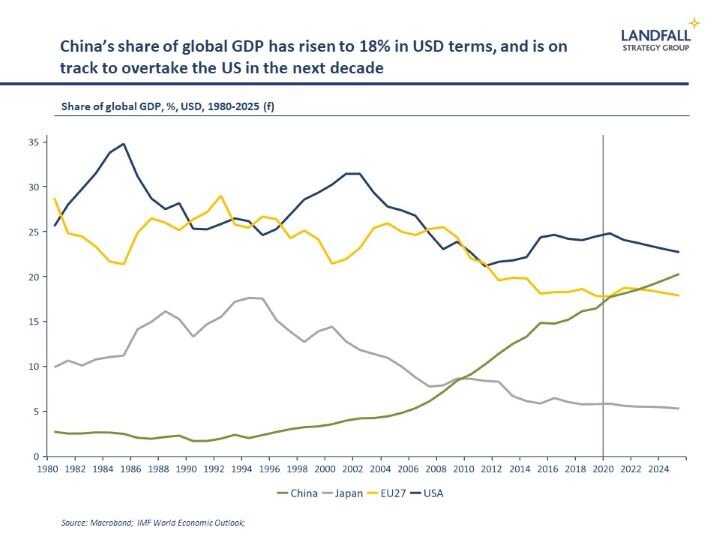

This reinforces China’s position as a key global growth engine. China has accounted for ~1/3 of global growth on average. And on current course and speed, China will likely overtake the US as the world’s largest national economy this decade (although there are many risks around China’s economic trajectory). China is the top export market for many economies.

In addition to its economic centrality, China is also a strategic rival to many Western economies. There is an increasingly statist approach to economic policy in explicit competition with advanced economies, including its new ‘dual circulation’ strategy (see this piece from James Crabtree); and China has markedly different interests and values (Hong Kong, South China Sea, Uighurs).

For some time, it has not been possible to separate the commercial relationship with China from the political relationship. The start of 2021 has provided several reminders of these tensions. China continues to block some Australian exports; the US has imposed new restrictions on Chinese companies such as Xiaomi; and tensions with China recently rose after the arrest of 50+ Hong Kong opposition members.

The political mood has shifted around the world, even (particularly) in countries exposed to China. China’s soft power has diminished due to its increasingly aggressive behaviour and threatening ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy.

Hard choices

Under current Chinese leadership these tensions will likely intensify not moderate. And as Martin Sandbu noted in the FT this week, ‘The biggest question in geoeconomics this year will be how the US and the EU develop their stances towards China’.

There is a reset underway in the West on China, with growing pushback. In the US, there has been a sea change in US policy approach towards China; this bipartisan hawkishness will endure beyond the Trump Administration.

And despite the EU’s recent investment agreement with China, there has also been a toughening approach in Europe – for example, restrictions on Huawei, greater scrutiny of inward investment.

This is even the case in traditionally liberal small economies, from Austria to Denmark and the Netherlands. Many are implementing tighter restrictions on inbound Chinese investment in strategic sectors, recognising that these are not commercial transactions – even nominally private Chinese companies are answerable to the Communist Party.

Several European governments have released formal China strategies over the past few years, which are notably tougher in tone. The Dutch strategy on China, for example, released in 2019, stated it would be ‘open where possible, protect where necessary’. Small economies recognise that a tougher stance is required, preferably in coordination with other EU members.

In contrast, it was Germany and France that pushed for the recent investment agreement – over the concerns of some smaller member states, who also have meaningful trade and investment relationships with China. Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, as well as Poland and Spain, publicly expressed concerns.

My sense is that smaller economies are taking a more hardline approach because they are more alive to managing external exposures. The experience of small economies being squeezed by China, from Norway and Sweden to the Czech Republic (or Hong Kong, as I recently discussed), is taken seriously.

Small economies do not want to put themselves in a position where bilateral political disputes will have a meaningful economic impact on trade flows or investment returns.

For Asian small economies, China is an important source of growth and many have significantly deepened their economic relationship with China. But they have also invested in regional institutions (ASEAN+, CPTPP, RCEP) and are building broader portfolios of economic and political relationships to provide greater strategic space. Singapore is a small country that is managing this balancing act well.

But exposures can’t be fully diversified away. For example, Australia and New Zealand have significant economic exposures to the state of their bilateral political relationships with China – a source of substantial strategic challenge.

These issues are relevant for firms as well. Understanding commercial exposure to national political relationships with China should be a priority.

Hard choices

The unfortunate reality is that there will be growing frictions with China and a greater fragmentation in the global economy. Hard choices will need to be made by governments and firms.

The realism on China shown by several small economies in Asia and Europe should provide guidance to some larger European countries. And similarly the small economy approach of disciplined engagement and diversification of relationships is a more useful approach than the unilateral trade wars and go it alone policy of the Trump Administration. A more joined-up approach to China between the US, Europe, and others is critical – as seems more likely under the Biden Administration.

Governments and firms will need to adopt a more hard-headed approach to economic and political engagement with China. The golden years are well behind us.

Get in touch if you would like to discuss this analysis and its implications. I am also available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors.

Chart of the week

Covid-19 vaccines offer the prospect of the normalisation of life and economic activity in 2021. But there is substantial variation in the speed of deployment across countries. Israel and the UAE are leading, along with the US and the UK, all of whom made rapid arrangements to access vaccines and then rolled out vaccinations quickly. In contrast, many European countries have low vaccination rates - with the Netherlands lagging at the bottom of the European rankings.

Small economies around the world

Dutch property prices offer a view on changing economic geography post-Covid: house price growth and transactions are weakening in Amsterdam, with reduced inflows and people moving to cheaper areas with more greenery – as working remotely takes hold. And in Singapore, the government is considering measures to moderate residential house price growth – even as Singapore’s commercial office market softens.

Taiwan is becoming more central to global economics and politics. In one of the parting acts of the Trump Administration, it lifted the restrictions on official visits between the US and Taiwan. And Taiwan’s dominance in the semiconductor space positions it as one of the commanding heights of the global economy.

Political disruptions in European small economies. The Dutch coalition government resigned last week on the back of a scandal about the administration of benefits (from 2012). But the Cabinet continue in caretaker mode until the elections in March, in which the PM’s party is expected to win the largest share. In Estonia, the governing coalition fell on a corruption scandal involving a far right party; a new coalition has been assembled. And a former Danish Minister is being impeached.

Singapore attracted a record S$17.2b of inward FDI in 2020, beating the previous record set in 2019. The EDB reported ‘large capital investments in the electronics, chemicals, and research and development sectors’ despite the challenging global economic context.

Amsterdam is attracting listings to its stock exchange, successfully competing against London post-Brexit. Although Brexit remains an overall negative for UK-exposed economies like the Netherlands, there is some scope for European economies to compete more effectively for economic activity.

Greece may be set for goldilocks status, with an ‘explosive recovery’ forecast for H2 2021 by a leading Greek bank. Greece was hard hit by the collapse in international tourism in 2020, but stands to benefit significantly from EU recovery funds. This Monocle interview with Greek PM Mitsotakis gives a good sense of the trajectory and focus.

Small economy currencies have strengthened through 2020, notably the NOK and NZD. And Taiwan’s central bank is also battling its strengthening currency, with significant inflows due to its high-performing technology sector.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling